CBS’s Jericho—the apocalyptic drama this blog’s been following—took some steps forward (in more ways than one) with last Wednesday’s episode, "Federal Response." (If you haven’t seen the episode and are still planning to, you might want to skip this post; you can watch this or any other episode here or read detailed summaries here.)

CBS’s Jericho—the apocalyptic drama this blog’s been following—took some steps forward (in more ways than one) with last Wednesday’s episode, "Federal Response." (If you haven’t seen the episode and are still planning to, you might want to skip this post; you can watch this or any other episode here or read detailed summaries here.)The apocalyptic-ness took a dizzying step forward at the end of the episode, with the ground rumbling and the townsfolk gazing upward at the night sky, horror-stricken as the contrails of two just-fired-from-the-ground ICBM missiles continued to lengthen across the skyline as they fly away from Jericho. That scene

resurrected those eerie vibes I carried around with me as a teenager growing up with The Late Great Planet Earth, Red Dawn and The Day After as the prophecies for our future. Seeing those missiles in the air was unexpected (perhaps a tribute to some good plot structure) and quite chilling.

resurrected those eerie vibes I carried around with me as a teenager growing up with The Late Great Planet Earth, Red Dawn and The Day After as the prophecies for our future. Seeing those missiles in the air was unexpected (perhaps a tribute to some good plot structure) and quite chilling.On the character front, while we don’t get Jake’s full story (like exactly what he’s been doing for the last five years that’s given him enough knowledge, skill and wherewithal to use explosives, shoot bad guys with dead-shot accuracy, and wire just about anything to do just about anything), we do learn (thanks to a look at a computer over the shoulder of that shadowy Hawkins) that he’s been spending a great deal of time traveling between South American countries and some middle eastern ones as well. Whatever Jake’s been doing, however, I don’t think it’s near as nasty as the stuff Hawkins must’ve been up to—or, at the very least, Jake isn’t as comfortable with that nastiness as Hawkins is.

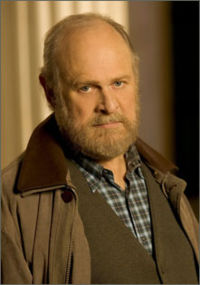

But more interesting to me is the step forward taken by the prodigal son motif, with Johnston Green (Jake’s father) finally acknowledging that his son had come home a changed and better man than when he left. (His acknowledgement, however, cuts off Jake confession of just what it is he’s been doing. Grrr.) In some ways, this echoes the father’s acceptance of the son’s return in the biblical Parable. But there’s a crucial difference: Johnston’s love is based on performance rather than unconditional. One feels sorry for Jake’s currently in-good-graces but over-achieving brother Eric; when their father finds out Eric’s sins, Eric’ll be the one out of grace.

But more interesting to me is the step forward taken by the prodigal son motif, with Johnston Green (Jake’s father) finally acknowledging that his son had come home a changed and better man than when he left. (His acknowledgement, however, cuts off Jake confession of just what it is he’s been doing. Grrr.) In some ways, this echoes the father’s acceptance of the son’s return in the biblical Parable. But there’s a crucial difference: Johnston’s love is based on performance rather than unconditional. One feels sorry for Jake’s currently in-good-graces but over-achieving brother Eric; when their father finds out Eric’s sins, Eric’ll be the one out of grace. Ironically, however, I think this is the kind of image many of us carry around of God—that his love for us is based on our performance. That if we mess up, somehow we have to earn our way back into his love, we have to prove by a series of actions (or penance) that we are worthy to be loved again. But the Parable says just the opposite. We don’t need to work our way back into God’s good graces. All we need to do is go home, a home that is not even a breath away. And so great is his love and lavish his grace and strong his longing for us that he’s waiting—always waiting—right there, already embracing us before even as we look up to see the gate.

Ironically, however, I think this is the kind of image many of us carry around of God—that his love for us is based on our performance. That if we mess up, somehow we have to earn our way back into his love, we have to prove by a series of actions (or penance) that we are worthy to be loved again. But the Parable says just the opposite. We don’t need to work our way back into God’s good graces. All we need to do is go home, a home that is not even a breath away. And so great is his love and lavish his grace and strong his longing for us that he’s waiting—always waiting—right there, already embracing us before even as we look up to see the gate.It’s like Kari at Healed Waters says:

He who knows all things I have ever thought or done, all things I am now thinking and doing, and all things I will think and will do, will never leave me nor forsake me. He will not abandon me because I stumble. He will not slam the door behind Him because I falter. He will not grow angry because I am frail and fearful. He reaches down to me in my present state, knowing what my present state will be in all future moments, and He touches me. He reveals Himself to me, and He comforts me. He reassures me. He delivers me. He saves me.Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying our actions don’t need to reflect our faith, our trust in God. If they don’t, then we’ve got a problem. Sin matters to God. Why? Because it destroys us. It hurts us. And as we live with him, God will work with us to uncover and shed off whatever sin threatens us. But, by the same token, our actions won’t count for much if we think they are what win us God’s favor and approval, that how we act and what we do (or don’t do) are what enable us to live in his Kingdom. Take a look at the elder son in the Parable. He lived with his father but didn’t get what it was all about. He thought it was his actions—his performance—that earned him his place. But he missed the point.

He is not finicky. He is not fickle. He is not moody. He does not wake up grumpy and He does not have bad days. He is unchangeable.

He is love.

He is my Heavenly Father.

And I, I am His child.

Forever.

And too often so do we. It isn’t about earning a place in the Kingdom. In fact, there’s no way we can ever perform well enough to earn a place in God’s Kingdom. Instead, it’s all about God’s love and grace. It’s discovering that life comes from and is meant to be lived with God. It’s not what we do that matters or earns us his love, but God love for us, his desire for us to know where home is, his longing for us to live in and experience the transforming power of his love as we live with and in him.

There’s a way to live in God’s kingdom, but it’s not based on how we behave. It’s based on being loved, then loving God and loving others. As we grow in our experience and understanding of being loved, as we believe and trust that God is who he says and can do what he says and base our life on that, then our actions are going to follow. But, in the end, we are not our actions—be they good performances or missing the mark. We are new creations, beloved children of God. The life we live—how we act and react—flows not out of actions-bent-to-please but who he’s made us: new creations thriving on his love, those paradoxically transforming already-but-not-yet folk of the Kingdom who make wrong choices yet turn around in the moment-of-dread-remorse to find the Father already meeting us, already embracing us, with love pouring abundantly and forgiveness already given.

That’s quite a bit different from Jake’s father. And that’s quite a bit different from how most of us treat each other. But it’s the way of the Father. It’s the way of the Kingdom. It’s the way of incomprehensible yet incredibly-here-and-now love. And when you decide to live in and trust love like that, it will not only transform you but spill into the space and people around you. Amen.

(Images: Jericho images, CBS; Batoni’s Return of the Prodigal Son, Wikipedia) jerichoctgy