Earlier this week, my husband and I watched the Johnny Cash bio-pic Walk the Line. The film covers the first part of Cash’s life, from his childhood in 1940’s Arkansas to his 1968 marriage to June Carter. Before the film, I didn’t know much about Cash’s background except that his walk with faith, sin, and redemption permeated his music and the interviews I read or heard. (In fact, it was an interview on NPR when his last album was released that actually inspired me to buy my first Cash album.) After watching the film, however, I looked at my husband and said, “Now I understand why he was the way he was.”

Earlier this week, my husband and I watched the Johnny Cash bio-pic Walk the Line. The film covers the first part of Cash’s life, from his childhood in 1940’s Arkansas to his 1968 marriage to June Carter. Before the film, I didn’t know much about Cash’s background except that his walk with faith, sin, and redemption permeated his music and the interviews I read or heard. (In fact, it was an interview on NPR when his last album was released that actually inspired me to buy my first Cash album.) After watching the film, however, I looked at my husband and said, “Now I understand why he was the way he was.”There’s three crucial elements—two portrayed strongly in the film and one only hinted at—that helped me understand and grow in respect for Cash (don’t read any further if you don’t want to be spoiled—I must admit, half the beauty of this film for me was knowing little if anything about Cash’s history before I watched it):

First, the film aptly portrays events in Cash’s childhood life that hung about his neck and pulled him down into drugs and alcohol and emptiness: the death of his older brother Jack (who loved and protected him) and a father who withholds his love. That’s more than enough demons to haunt one man.

The second element is June Carter, herself leading a troubled life (married and divorced twice before she marries Cash at the end of the film) but with parents (apparently of strong faith) far more loving, supportive and mentoring. It is June (and her hinted at faith in God) that pulls Cash back from certain death as he’s almost pulled under by the weight of demons. (This is aptly portrayed in the film as Cash—both high and drunk and reeling from another rejection by his father—rides atop a mired tractor as it slides backwards down a hill and into a lake. June, moved by her love and urged on by her parents, literally pulls him out of the water. According to Wikipedia, the actual event that precipitated his recovery was much more harrowing.) I was delighted with the portrayal of the fierce strength of love, as June and her parents (her father pointing and ready to fire a shotgun) chase a dealer off Cash’s property as he’s detoxing in an upstairs bedroom.

The third element, which many reviews have already detailed as missing from the film (including this one from Christianity Today), is Cash’s own faith. The last few moments of the film reveal in an almost passing, understated scene a dramatic change that’s taken over Cash. If you didn’t know about his faith, you’d assume it was all June’s love that did the changing. While I get the filmmaker’s take that Cash was more running from God than to him during those years, I wish I could have seen more of role of faith and God in that change.

All three of these elements made Cash who he was (and, if we're honest, ourselves?): the consequences of the sins made against us and those we commit on our own, the power of the fierce love of God’s people and a God-formed community, and the legacy of a choice to surrender to God instead of the world. It’s not all tied up at the end of the film, and I don’t think I’d want it to be. Cash’s life wasn’t like that—and in many ways, that is what attracts me to his music and walk with God—and neither is ours.

I ran across another way to look at this nestled in a column in the March/April issue of Relevant Magazine (passed to me by my neighbor Kelli—and another reason I’ll miss her when she moves next week, sigh). Dan Haseltine (lead singer of Jars of Clay) writes:

There is a scene in Walk the Line . . . that has given me permission to think differently about art, music and the Gospel. After listening to Johnny Cash sing a gospel standard, Sam Phillips sets the tone for Cash. “If you were about to die, lying in the gutter and you had one song to sing, one chance to tell God and man what you thought about being on this earth and being alive . . . Is that the song you would sing?” Is that the way you would communicate the story of humanity, the way you would describe the world? To Sam Phillips, Cash’s trite old gospel song was not believable. That same gospel song is still not believable.Johnny Cash was the "walking wounded" and the "perpetually healed." The film showed the walking wounded astoundingly well, though I wish it had showed more of the perpetually healed, too. But then, we have Cash’s music, interviews and life for that. More to the point, we have our own. Therein, for me at least, lies the challenge: to share myself wounded and broken while healed and whole. To live broken and redeemed.

There is a weight to the Gospel. There is a mass connected to the story of redemption. It is the dark places—the addictions to pornography, alcohol, drugs, power and control. It is in our propensity to blame and abuse each other, our greed and our depravity. It is the substance of these things that gives us a place to speak about the slow road to recovery.

When we find the Gospel to be true and start to wrestle with the implications, it eventually brings us to a place where we must confront our humanity and know ourselves as both the walking wounded and the perpetually healed.

Enough rambling. Blessings.

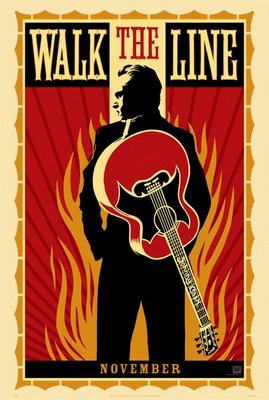

(Image: 20th Century Fox; from Wikipedia’s Walk the Line, itself worth the visit)