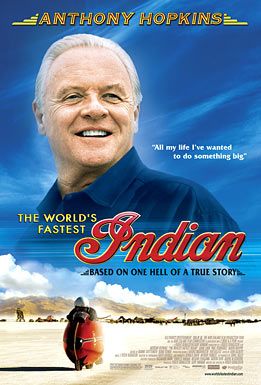

For the life of me, I can’t remember how The World’s Fastest Indian landed in our Netflix queue, but it arrived in the mailbox and settled into our DVD player this weekend—and (even according to my husband and brother-in-law) it was a really good flick.

For the life of me, I can’t remember how The World’s Fastest Indian landed in our Netflix queue, but it arrived in the mailbox and settled into our DVD player this weekend—and (even according to my husband and brother-in-law) it was a really good flick.The film, set in the 1960s, is based on a slice of the life of New Zealander Burt Munro, who (according to NetFlix’s jacket) “set records with his customized Indian Scout motorcycle at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. But perhaps more amazing than his jaw-dropping land speed of 183.586 mph was the fact that he was a 67-year-old grandfather.” The film takes liberties with Munro’s life, but (according to wikipedia and fan sites out there) expertly captures his eccentric, charming, tenacious (and apparently womanizing) personality.

Except in the film’s opening scene of shelves crowded with engine parts labeled “OFFERINGS TO THE GOD OF SPEED,” literal God-talk is virtually absent from the film—but this film has faith written all over it. Hollywood Jesus’ Darrel Manson sums up this aspect of the film well:

Burt has given his life over completely to the god of speed. He is not just a mechanic tinkering with the engine. He makes all his own parts in rather unorthodox ways. He has turned his life over to this machine as he molds it into what will give him that ultimate speed.While faith in this film isn’t set on God, it nonetheless brilliantly displays the results of what happens when we—with all we are—step out on what we believe. It reminded me of the radical and abandoned obstacles-become-opportunities kind of faith we are called to as Christians. If Christians committed to Jesus the way Burt committed to speed, that light-on-a-hill that Jesus says he shines through us would be utterly blinding.

Burt is something of a holy fool – one who, in the pursuit of their god, acts in ways that seem strange and foolish. In many ways, he is an innocent. He has no guile. What you see is what you get and what he sees is what he accepts. . . . Burt . . . is a true believer – in speed, and in himself. And his faith is well founded.

The film also reminded me (in a Plato-shadow-on-the-cave-wall kind of way) of Chariot’s of Fire and Eric Liddell’s description of why he runs: “I believe God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast. And when I run I feel His pleasure.” A similar (albeit more earthly) feeling seems to follow in Burt’s wake. He exhibits an uncanny ability to intuit machines. From his old motorcycle to the sputtering cars of a used-car salesman (wonderfully played by Paul Rodriguez), Burt makes them hum and race and do all they were created to do (and more)—and that brings delight, awe and joy not only to Burt but to everyone around him. As he’s faithful in using his gift, a greater gratification than just his own is born and swells. That, I think, may be the nature of gifts. They’re God-given. When they’re used, how can the help but bring joy?

Finally, another aspect of the film that resonated with me was the rippling effect of Burt’s faith in a world where people support rather than discourage each other. In the film, jaded folks on the fringes of society—a brash biker youth, a hotel clerk, Rodriguez’s used-car salesman, sailors he cooks for—are softly changed when they encounter Burt. Then there’s the racing folks gathered at Bonneville, who don’t even know how blinded they are by rules and regulations until little encounters with Burt break them free bit by bit—and they witness pure speed beauty as a result. (Heh, it reminds me a bit of how encounters with grace can break down our bent towards law, leaving us in the midst of sheer glory.)

Bottom line, the film illustrates the power of faith and the power to change your own corner of the world. In real life, this is multiplied over hundred-fold when our faith is in God—when we embrace and trust him, live in and allow him to live through us, when we are authentic with our failures and our dreams and our longings under his love. The kingdom just explodes and lives change in radical and eternal ways.

(Images: Magnolia Pictures)