So, last month, I’m making myself comfortable in a cushy, high-backed chair on the set where we’re about to tape May’s segment of the monthly locally televised book club that I participate in nine months of the year (we take a break for the summer). There’s only three panelists for this segment: me (who feels like I fake my way through each of these tapings), Lauren (our young, talented, smart and beautiful moderator who doesn’t have to fake intelligence) and Shane (the guest panelist that month who’s one of my church’s ministers and, I must admit, one of the most gifted persons I know when it comes to Scripture and its application).

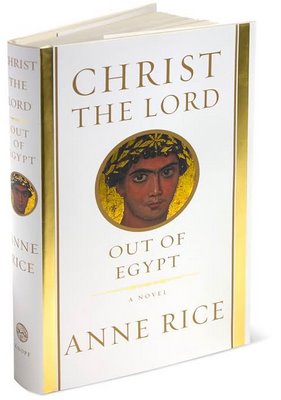

So, last month, I’m making myself comfortable in a cushy, high-backed chair on the set where we’re about to tape May’s segment of the monthly locally televised book club that I participate in nine months of the year (we take a break for the summer). There’s only three panelists for this segment: me (who feels like I fake my way through each of these tapings), Lauren (our young, talented, smart and beautiful moderator who doesn’t have to fake intelligence) and Shane (the guest panelist that month who’s one of my church’s ministers and, I must admit, one of the most gifted persons I know when it comes to Scripture and its application).We’re getting settled on the set and trying to find the right place to hook our microphones onto our shirts. It’s a few minutes away from the cameras rolling, but we’re already talking about that month’s book: Anne Rice’s Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt, a novel that focuses on one year of Jesus’ childhood when he and his family return from Egypt and settle in Nazareth. We all liked the novel (though me more than them), think Rice did an excellent research job, and agreed that the novel sticks fairly close to biblical text (no heresy, in other words).

Then I discover that my opinion about one part of the book is definitely in the minority. I think Jesus could have showed some of the signs of his divinity in his youth as Rice suggests (healing people, showing influence over nature, etc.), but Shane—six years my junior, I might add—disagrees. We argue a bit, me thinking Jesus’ childhood stunning-the-temple-priests-episode indicates the possibility and Shane thinking Jesus wouldn’t showboat or use his power without forethought or reason. I’m a bit perplexed—not because I’m beginning to think I’m wrong (heh, I still don’t think I am) but because I suddenly realize that Shane’s got more clout than me in the public eye.

I whine, “I can’t disagree with someone who has a seminary degree. No one will believe me.”

“Sure, you can,” Shane says reassuringly. Then he grins, “But you’d be wrong.”

Heh. Funny guy.

Anyway, this is the type of novel that brings up discussions like that—which is why I highly recommend it as an addition to your own bookshelf.

The book made lots of waves when it was published last year, mostly because of Rice’s renowned reputation created by the vampire books she penned last century. She was long-departed from the Catholic Church and faith of her youth and was married to an atheist. But that all began to change in the 1990s and early 2000s, when through a several-year process she returned to the Catholic Church. A big part of that process was struggling through the illness and death of her husband while undertaking the in-depth research she put into this book. In the end, she came to conclusion that Jesus had to be who he said he was.

The book made good reviews both in the secular press and Christian media, both of which attest that it’s well-researched and written. Because of this research, one of the novel’s greatest strength is also one of Rice’s greatest demonstrated strengths as a writer: she puts us smack dab in the middle of the time and space in which Jesus grew up. I can see the house in which Jesus might have lived in Nazareth. I can see the tree in the courtyard, the hills above the house, and the Roman soldiers on their horses. I can feel the press of the crowds in Jerusalem and the cool water of the Jordan River. In addition, Rice’s detail-rich portrayal of the Jewish culture and family life deepened my understanding of why the Early Church could be the way it was—and made me long all the more for that today. In this novel, Rice writes the time and place and space of Jesus into existence for us today, and that’s a real gift in itself.

The other thing I appreciate about the novel is the reference to and expansion on some of the idioms of the time and historical traditions. Almost in passing, she gives us a greater understanding about what Jesus meant by “living water” and deepens my understanding of the Good Samaritan parable. Also, she gives this blogger a reason to reconsider the traditional idea of Mary’s perpetual virginity (as Scot McKnight is discussing over at Jesus Creed—also worth following).

Finally, the Author’s Note at the end of the book is a gem in and of itself. Essentially, it’s Rice’s testimony and experience with the Hound of Heaven. In addition, her analysis of the state of biblical scholarship is priceless.

It’s worth the read. I give it at least 3.5 stars.

(Image: Barnes & Nobles)