Um, this is a bit of film news I wasn’t sure whether or not to post. Cough. Er. Sigh. Well, here goes: ComingSoon reports Warner Bros is bringing Conan the Barbarian back to the big screen.

Um, this is a bit of film news I wasn’t sure whether or not to post. Cough. Er. Sigh. Well, here goes: ComingSoon reports Warner Bros is bringing Conan the Barbarian back to the big screen.What the heck is that piece of news doing on a God-talk blog? Bear with me a bit.

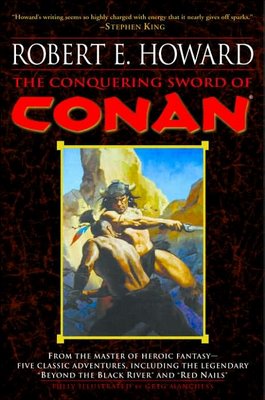

You may remember (then again, you may not) a couple of former go-arounds with the barbarian bloke in a pair of Arnold Schwarzenegger films. This time, however, the work is said to be aiming at staying closer to author Robert E. Howard’s original work as published in the 1930s as a series of novelettes and novels in pulp magazine Weird Tales.

Now, God isn’t all that present in Howard’s universe. In fact, Crom (the fictional deity of Conan’s people) is distant and gloomy. Also, consider this from Wikipedia:

Here’s another quote from one of Howard’s novels (courtesy of Wikipedia as well):The Conan stories are informed by the popular interest of the time in ideas on evolution and social Darwinism. Are some peoples destined to rule over

others? Are our physical and mental characteristics the result of our experiences or our inheritance from our ancestors? Is human civilization a natural or unnatural development?As Conan remarks in one story: Civilized men are more discourteous

than savages because they know they can be impolite without having their skulls

split, as a general thing. (Howard, The Tower of the Elephant, Weird Tales, March 1933)

Let teachers and priests and philosophers brood over questions of reality and illusion. I know this: if life is an illusion, then I am no less an illusion, and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and I am content. (Howard, Queen of the Black Coast, Weird Tales, May 1934).Now, there are a great many people today who still resonate with the character and Howard’s universe. Why? According to ComixFan, here’s the opinion by series writer Kurt Busiek:

. . . the core appeal of Conan is that he's his own man: passionate, powerful, unfettered and untamable. He's the pure barbarian, unsullied and uncorrupted by the taint of civilization, and he goes up against entrenched power, and he wins. Is that something that gets outlived? I don't think so. I think Conan taps into human nature, into that part of anyone who feels pushed around, controlled or compromised, and provides a release of that frustration. Here's a guy who doesn't take any crap, and who not only gets away with it, but also conquers the people trying to drag him down, make him like everyone else. How does that appeal today? Well, Conan's in many ways a child of the Great Depression, and I think it's no coincidence that he was revived again in the conformist Fifties and in the Seventies, at a time we'd lost faith in the "rules." Conan thrives when people feel frustrated, put upon or powerless. And there's certainly a large audience of people like that today.So, finally, here’s where we get to why this ended up on a God-talk blog. While Howard’s universe doesn’t say much about God-as-he-is, it certainly seems to say a heck of a lot about the culture in which we make our way through each day and at least one concept out there of who God is (or isn’t). And that, in a round-a-bout kind of way, brings God-talk into the open spaces—especially for those of us who follow Jesus, because we are the ones that Jesus asked to shine so bright in the darkness that the world might come to know who he really is. If we aren’t doing that (and the world is hungry for it), this is a good opportunity to ask why not—and figure out how it is we should live together and with our neighbors. In other words, this is one more chance to ask: how should we do church? What does is it look like to love God and love others? Those are questions this blog is asking quite often these days.

Well, that’s enough (or, as some of you are probably saying, more than enough) for now.

(Image: Barnes & Noble)